Transformational health project will help medical providers understand why chronic diseases disproportionately affect Black populations in Canada

May 19, 2025

Black people are often underrepresented in genomics research, resulting in biased findings and potential negative health outcomes.

To enhance representation and address disparities, a groundbreaking research project focused on improving precision medicine for chronic diseases among Black communities in Canada has received significant funding.

‘Genomic Evidence for Precision Medicine for Selected Chronic Diseases Among Black Peoples in Canada’ was approved for up to $17.6 million over four years with Genome Canada contributing up to $8.3 million.

Genome Canada approached the Canadian Black Scientists Network (CBSN) to consider developing a proposal addressing the issue.

Led by McGill University Department of Pediatrics professor and CBSN co-founder & program lead Loydie Jerome-Majewska, McMaster University cell biologist & cancer researcher Juliet Daniel, Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine professor OmiSoore Dryden and Upton Allen who is SickKids Hospital Infectious Diseases division head, the project represents a significant step forward in ensuring equitable healthcare solutions through cutting-edge research.

The genome, or genetic material, of an organism is made up of a unique DNA or RNA sequence. Each sequence is composed of chemical building blocks known as nucleotide bases. Determining the order of bases is called ‘genomic sequencing’ or, simply, ‘sequencing’.

“To do this well, researchers need to study the DNA and health information of people from all backgrounds,” said Jerome-Majewska whose lab utilizes mouse models to investigate the genetic and cellular mechanisms underlying morphogenesis during embryonic development. “Right now, most genetic studies do not include many people of African ancestry. This means that we don’t have enough information about how diseases and treatments affect Black people. Some treatments might not work as well for them. Our project wants to fix this gap.

“There is this dearth of data on the Black population when you look at sequencing and genomic data in the world. I look at babies with problems in their genome and I am always asked if it is the same for Black babies. I am unable to provide an answer because the data is not available. One of the reasons, I think, is that people just don’t invite Black people into the space to take part in these projects. The other reason is that Black folks, for good reason, do not trust the system and do not participate in the process.”

The American Association for Anatomy fellow said transitioning from symptom-based treatment to personalized medicine based on individual genetic profiles and shifting the focus in healthcare to genomic-level understanding of organisms are a game-changer.

“I am already in the process of starting a community advisory group,” Jerome-Majewska noted. “Having input from people who are Black who understand the system and can speak to whether or not the community want to participate in these types of projects is important.”

The project aims to sequence 10,000 genomes (short reads) from Black people, including African Nova Scotian communities in Canada with a focus on the clinical phenotypes of hypertension, adult-onset diabetes and triple negative breast cancer.

A total of 5,000 people from Ontario, 3,000 from Quebec and 2,000 Nova Scotians will be sequenced.

“The reason we selected these provinces is because they are where we find the Black folks in Canada,” added Jerome-Majewska who joined McGill University in 2005 and was the recipient of the 2023 International Society for Differentiation Anne McLaren Award for Outstanding Women in Development Biology. “We want to make sure we hit as many diverse communities as we can.”

In addition to these 10,000 genomes, 1,100 genomes will be studied, using long-read sequencing.

“This sequencing project will help us better understand why chronic diseases disproportionately impact Black Canadians,” said Daniel whose lab focuses on the transcription factor Kaiso that was first identified as a specific binding partner for p120 catenin that is aberrantly expressed or absent in human breast, colon and skin carcinomas. “Closing the gap and moving the needle will not be seen for another six or seven years. We will analyze the data, publish and write policy recommendations to the Ministry of Health before we get to that point. The whole idea is to create a Pan-Canada database that reflects the diversity of the Canadian population.”

Dr. Juliet Daniel (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

Dryden is excited to be part of the project.

“Genomes and Genomics sequencing can seem complex to many people because they involve huge amounts of data and specialized tools,” said the former James Robinson Johnston Chair in Black Canadian Studies at Dalhousie University. “By not having a more fulsome sequencing of people, especially when you are thinking about creating better and much more effective prescription drugs, we are missing the mark. If we can increase the diversity of people whose genomes have been sequenced, it means we will have a better ability to create medications for triple negative breast cancer, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes. That means Black communities will benefit.”

While individuals do not own their genomic data in the traditional sense, Dryden hopes Black communities will have greater control and benefit from genomic research.

“There needs to be a well-planned-out protocol around how Black people’s genomes will be used in these development projects,” added the interdisciplinary scholar whose 2016 doctoral dissertation examined how blood donation rules discriminate against certain populations. “That is work that Genome Canada needs to engage in. They need to think through clearly how Black people’s DNA and genome will be interpreted, analyzed and used. There must be data governance and responsibility for Black communities across Canada to ensure an anti-racist lens is used when it comes to sharing their data.”

Dr. OmiSoore Dryden (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

The transformational project is part of a $200 million Canadian Precision Health Initiative (CPHI) with $81 million in government funding expected, including co-funding from industry, academia and public sector partners.

The CPHI will build Canada’s largest ever collection of human genomic data – more than 100,000 genomes representing the diversity of Canada’s population.

The landmark collaboration will help transform health care in Canada by unlocking genome sequencing data for more personalized, preventative and cost-effective care. It will also sharpen Canada’s edge in the highly competitive health innovation sector.

Precision medicine is a new way of treating and preventing diseases by focusing on a person’s unique genetic makeup and other personal factors. It has the potential to improve healthcare by helping doctors diagnose diseases more accurately, finding health problems earlier and choosing the best medicines and treatments for each person or group of people.

“This is key,” said Allen who led a team that looked at a cross-Canada initiative to sequence the DNA from a large number of individuals infected with COVID-19. “As we move forward, medical treatments will be tailor-made to suit an individual’s characteristics. What is happening now is that the data generated that will guide that process is lacking in terms of the genetic sequencing information needed to make that relevant to the Black population. If a treatment is designed for us in the next three to five years and the data is not available to create that design, then we will be left behind.”

Dr. Loydie Jerome-Majewska (l), Dr. Upton Allen & Dr. Juliet Daniel (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

The essence of personalized medicine lies in tailoring healthcare interventions to an individual's unique characteristics, including their genetic makeup, lifestyle and environmental factors.

“If a Black person and a White individual undergo a kidney or heart transplant and both of them get the same medication or same dosage to keep their immune systems from rejecting the organ, the chances of the Black person rejecting that organ are greater,” said Allen who is the BlackNorth Initiative Health Committee co-chair. “Also, with the emergence of artificial intelligence, we can create more tailor-made treatments more rapidly.”

Powered by AI and shaped by a diverse coalition from across the public sector, industry, academia, health care, patient groups, Indigenous organizations and non-profits, the initiative aims to generate maximum impact.

In a Canadian first, the CPHI will build a public genomic data resource that reflects the nation’s diverse population. This will ensure precision health innovations benefit all and position Canada as a global leader in representative genomic data collection.

While the Black-led project focuses on adults 18 years of age and older, Daniel said the results will be of relevance to all age groups of Black persons in Canada.

“Our project is truly assembling the building blocks to transform medical care for Black Peoples of Canada through precision medicine,” pointed out the CBSN co-founder and Strategic Advisor to the President for the Canada-Caribbean Institute at McMaster.

A community lens is critical in any research focusing on Black people to ensure ethical, equitable and culturally sensitive practices.

As a collaborator on the project, York University professor Carl James brings that perspective to the research.

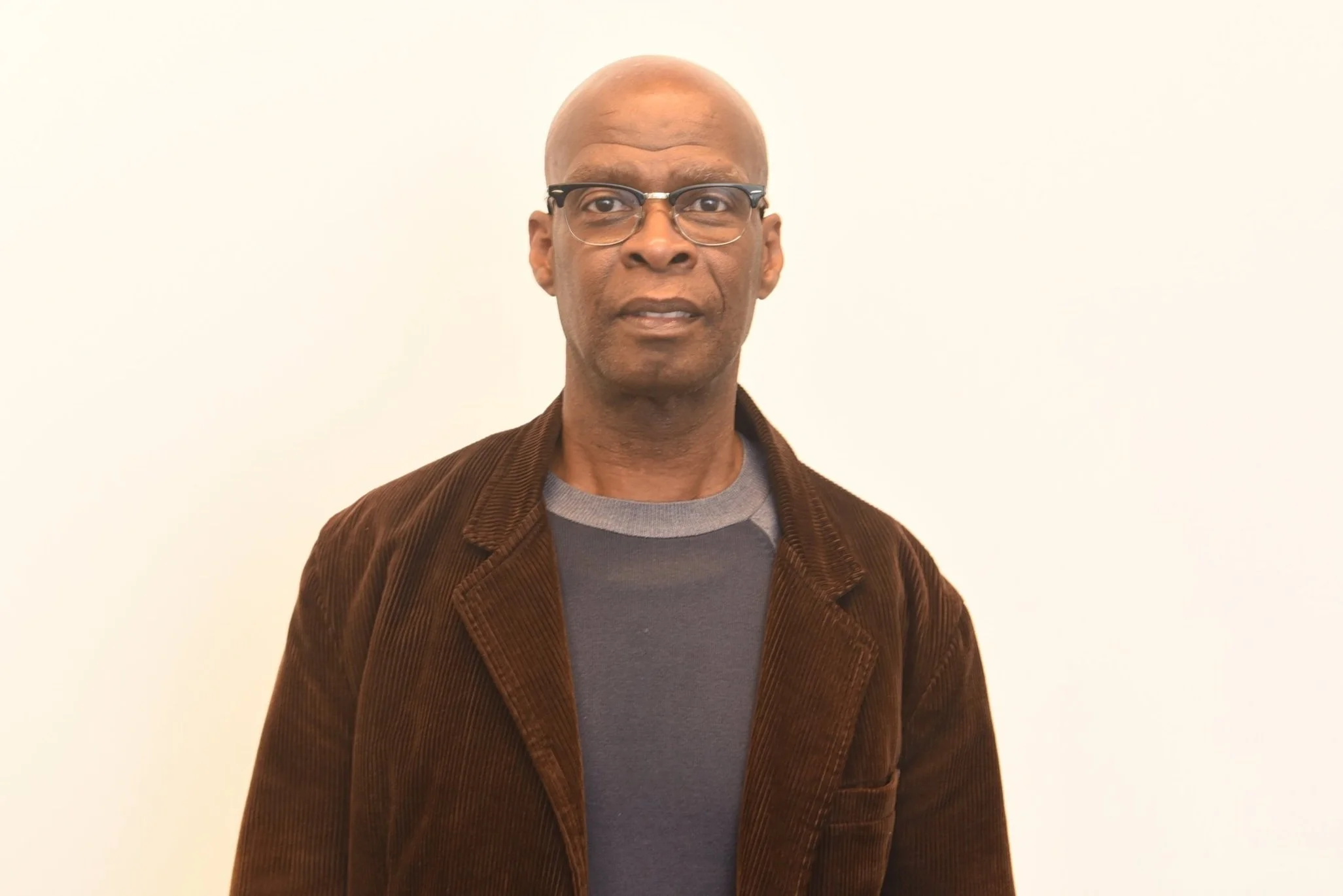

Dr. Carl James (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

He holds the Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community and Diaspora in the Faculty of Education at York University where he is also the Equity Advisor to the dean.

“Anything that addresses the needs of Black people in Canada is welcome,” said James. “At the moment, there are significant gaps when it comes to the health of Black Canadians. We also have to factor in that there is a history of medical abuses rooted in systemic racism that has caused Blacks to be reluctant to take part in the medical system. To ensure that Black patients understand their medical care, healthcare providers must focus on cultural competence, building trust and addressing historical biases. That is something I will be keeping a close eye on during this process.”