Joe Halstead co-founded the Bristol West Indian Cricket Club 60 years ago

October 26, 2025

In the 1950s, about 1,000 Caribbean migrants were living in Bristol. By 1962, this number had grown to roughly 3,000, many of whom were part of the Windrush generation, invited to Britain to help rebuild the country after World War II.

Upon arrival, they faced widespread racism and discrimination. Finding decent housing was difficult, and there were limited employment opportunities. Despite these challenges, the community found comfort and enjoyment in cricket which became a central part of social life.

Joe Halstead grew up in Jamaica without knowing his father. His single mother, who was raising two other sons, could not afford to send him to high school, and he did not have the grades required for admission.

He arrived in Bristol in 1960 and quickly became part of the Black community which often felt excluded from wider society. For him and others, weekends were a time for social and cultural gatherings, with cricket at the heart of these community connections.

“Because there were so few of us, we stuck together and did everything as a group,” Halstead recalled. “We joined clubs since we didn’t have our own team. A few talented Caribbean players were skilled enough to make those teams.”

As the number of Black cricketers increased across the southwest English city, the idea of forming a dedicated West Indian team became inevitable.

It was Jamaican-born Austin Smith who first conceived the idea for the team, recognizing the need for a space where Caribbean players could come together, celebrate their identity and play the game they loved on their own terms.

“One Saturday afternoon during the winter, about six or seven of us got together at his home and said, ‘Let’s do this,’” Halstead, who attended Bristol Technical High School, recounted. “We knew we were going to get pushback from the league and that some Caribbean players might not want to be part of it. But we had an excellent discussion.”

As expected, their initial application to join the Bristol & West Cricket League was rejected.

“They said we had to have been playing for two years before they would even consider us,” said Halstead who was an opening batsman. “That wasn’t unusual, and we respected it. We did not have a ground and a clubhouse which were requirements. After matches, it was common for players from both sides to socialize over a beer, but we didn’t have a facility to accommodate that. Nevertheless, we got together and played friendly matches on Sundays at Eastville Park.”

Because of the overwhelming support they had gained and their competitiveness, their application was approved the second time around.

The Bristol West Indian Cricket Club played its first league game in 1965, with Halstead captaining the team.

“It was quite an exciting time,” he said. “We played good cricket and we had a large following.”

Back then, touring teams played matches against county sides before or during a Test series.

The three-day match between the West Indies and Gloucestershire in July 1966 at Ashley Down Ground was a significant event for Bristol’s Caribbean community, especially for Halstead whose schoolmate was on the team.

He and fast bowler Rudolph Cohen were classmates in junior school in Jamaica.

“After the game, I took him to the Bristol West Indian Cricket Club where everyone was happy to welcome him,” said Halstead. “I was thrilled to see my friend and to make him feel at home.”

Cohen, who was 23 and the youngest member of the touring party, joined the team as a late replacement for Lester King who was recovering from injury. Although he never played in a Test match, he later pursued a legal career in Connecticut.

The late Joyce Stephenson, wife of civil rights activist Paul Stephenson who died in November 2024, pours a drink for Joe Halstead at his farewell reception at the Bamboo Club in Portland Square in October 1967 (Photo contributed)

While Smith, who now resides in the United States, came up with the idea to start the club, Guy Bailey did most of the hard work to make it happen.

At age 16 in 1962, he left Jamaica to live with an aunt and get a better education.

Fascinated by the double-decker bus, Bailey applied for a conductor position but was denied because of his skin colour.

This injustice sparked outrage in the local community, and with him at the centre, they organized the Bristol Bus Boycott in 1963, a pivotal protest that challenged segregation and helped pave the way for Britain’s Race Relations Act.

Like many Caribbean people in Bristol at the time, Bailey loved cricket and played a major role in getting the club up and running.

He secured funding from the Lottery Fund and the Sports Council for the Rose Green Sports & Leisure Centre which is the club’s home. In 2013, it merged with Phoenix West Indian Cricket Club and is now known as the Bristol West Indian Phoenix Cricket Club.

“Guy did a lot of the administrative work to get the plans drawn up for the clubhouse,” said Halstead. “He deserves a lot of credit because he stayed the course.”

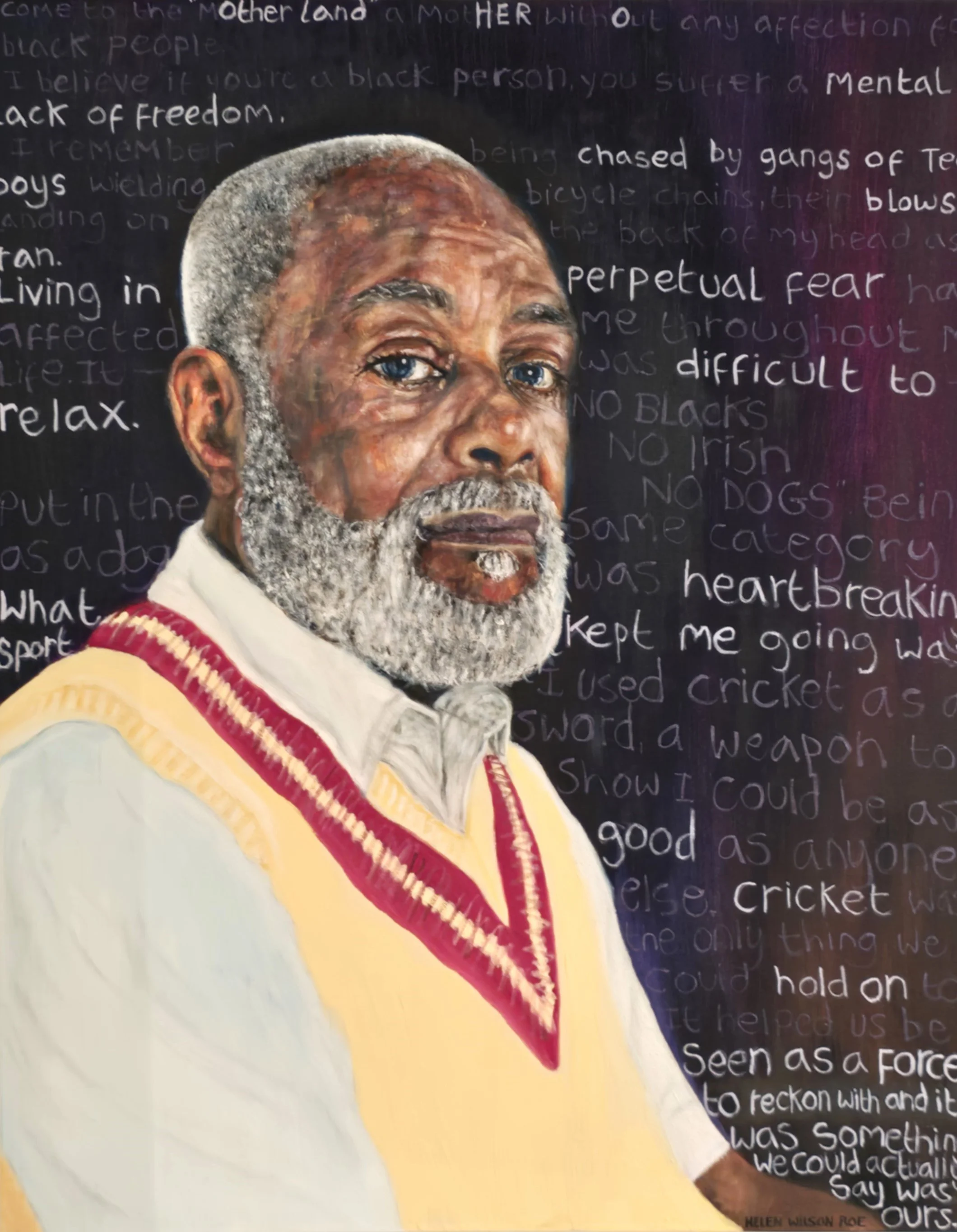

In November 2024, a portrait of Bailey was unveiled at the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) Museum at Lord’s.

Guy Bailey’s portrait at Lord’s

Helen Wilson-Roe, a Black artist from Bristol whose work includes a statue of Henrietta Lacks that was erected at the University of Bristol four years ago, painted the portrait of Bailey who the University of the West of England Bristol awarded an honourary degree last year.

“The establishment of the cricket club stands as a testament to Guy Bailey’s never-ending resolve to ensure that cricket remained a fixture in the lives of all British people, irrespective of their race or religion,” she said at the unveiling ceremony. “I have made it my mission to paint portraits of individuals who have consistently contributed to their local or global communities and have brought about meaningful change, yet have been overlooked.”

Bailey’s portrait is part of the ‘England’s Black Cricketers’ exhibition at Lord’s, displayed alongside images of iconic Caribbean players such as Sir Garfield Sobers, Viv Richards, Brian Lara and Michael Holding.

Created by artist Justin Mortimer, this portrait of Brian Lara hangs in Lord’s pavilion

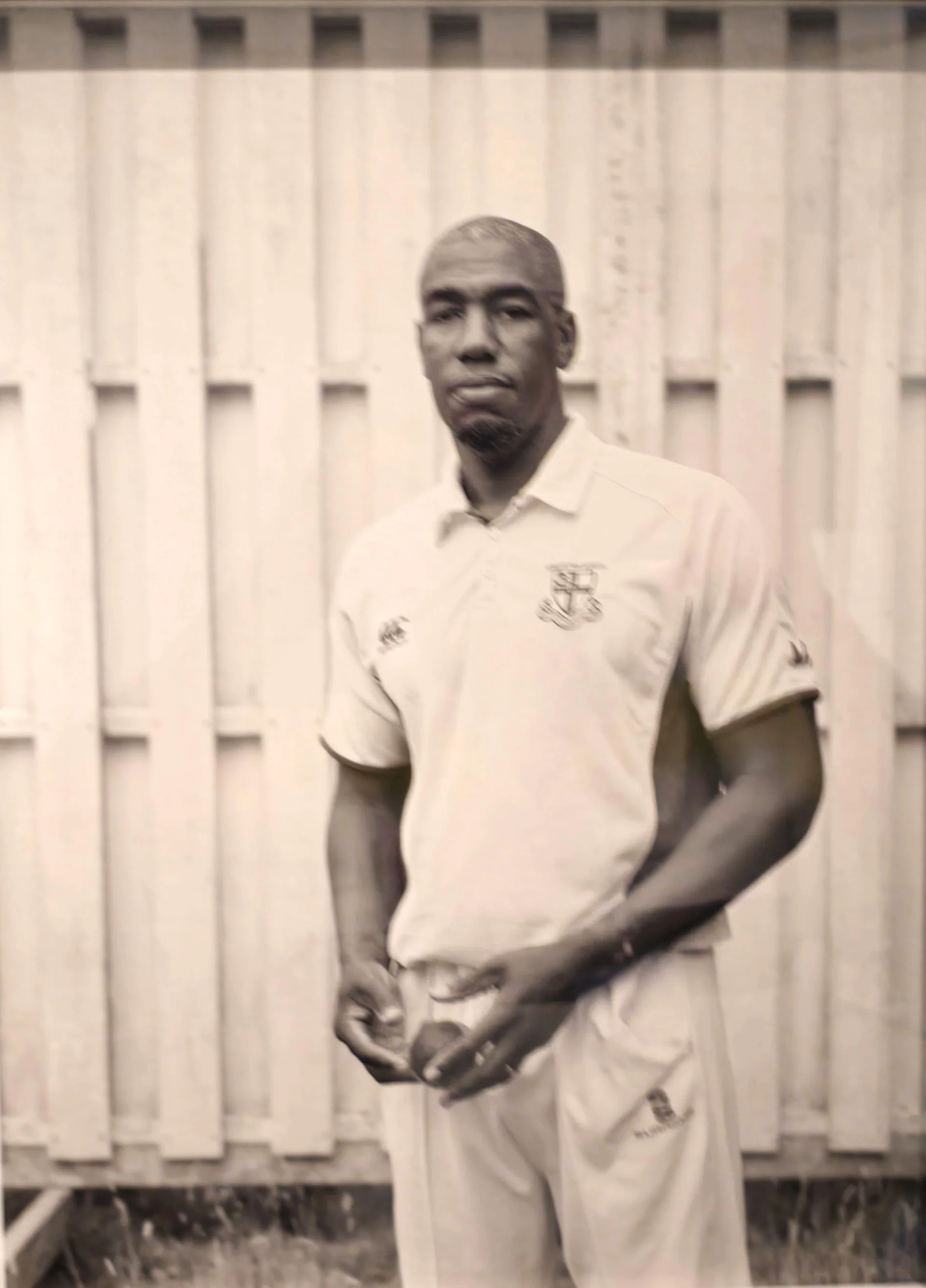

The exhibit contains portraits of the 21 Black cricketers who have represented England.

“This project is a celebration of them and their achievements,” said photographer Tom Shaw. “Hopefully, it will act as an inspiration to young Black cricketers.”

Roland Butcher made history in March 1981 when he became England’s first Black cricketer. Fittingly, his debut took place in Barbados, the island where he was born and raised before migrating to England in 1967 at the age of 13. Over his international career, he went on to play three Test matches.

Ebony Rainford-Brent became the first Black woman to play cricket for England in 2001 and was a key member of the team that achieved a remarkable “triple crown” in 2009, winning the ICC Women’s World Cup, the ICC Women’s World Twenty20, and retaining the Ashes. Beyond her playing career, she has become an influential voice in cricket media, contributing to Test Match Special and Sky Sports commentary while promoting inclusivity in the sport through her work with Cricket for Change and as Chair of the Active Cricket Engagement program charity.

Dominican-born Phillip DeFreitas made his Test debut for England in Australia at the age of 20 during the 1986–87 Ashes series. Over his Test career, he appeared in 44 matches, taking 140 wickets and scoring 934 runs. The all-rounder also represented England in 103 One-Day Internationals, where he claimed 115 wickets and added 690 runs with the bat.

Fracturing his kneecap while running in to bowl during his fifth Test against New Zealand in Wellington in 1992 brought an abrupt end to David Lawrence’s international cricket career. The powerfully built fast bowler passed away in June 2025 at the age of 61.

Born to Barbadian immigrants, Alex Tudor represented England in 10 Test matches. The highlight of his career came in his third Test at Birmingham in 1999 when he scored an unbeaten 99 as a nightwatchman -- the highest score ever made by an Englishman batting at that position -- to help his team defeat New Zealand by seven wickets. Batting at number nine in the first innings, the medium fast bowler was unbeaten on 32.

Born in Guyana, Chris Lewis played 32 Tests and 53 One-Day Internationals for England between 1990 and 1998. The all-rounder scored his only Test century on his 25th birthday in 1993 in Chennai.

The exhibit pleases Halstead.

During his time in Bristol, there were no Black English international cricketers, so the visibility and recognition of Black players highlight how far the game has come in terms of diversity and representation. It’s a reminder of both the challenges of the past and the progress being celebrated today.

Bristol West Indian Cricket Club founder Austin Smith (r) presents a trophy to Joe Halstead on behalf of the club members at Halstead’s farewell reception in October 1967 (Photo contributed)

After six years, Halstead and his wife of 54 years, Norma Halstead, who was a nurse practitioner, came to Canada in 1967.

“My time in Bristol was fulfilling,” the club’s honourary life member said.

In 24 years with the Ontario government, Halstead worked in five Ministries and held several management roles, rising to the position of Assistant Deputy Minister in the Ministry of Culture, Tourism & Recreation.

He was the province’s key figure in three bids to bring the Olympic Games to Toronto and served as Vice-Chair of the bid committee that secured Toronto as the host city for the 2015 Pan Am Games. He also played a significant role in helping Toronto get a National Basketball Association (NBA) franchise.