Dahrran Diedrick touched lives beyond the football field

December 18, 2025

Losing a child is devastating, but losing your only child reshapes life in a way nothing else can.

For Karen Moulton, the grief strikes like a sharp, sudden pain, sometimes even stronger than childbirth, because all the love she carried had just one place to belong.

When former Canadian Football League (CFL) running back Dahrran Diedrick succumbed to cancer in June 2023, her world stopped.

“Being my only child, he was exceptional and unique,” said Moulton. “He was kind, considerate and the kind of child every parent would wish for.”

Karen Moulton and her late son Dahrran Diedrick (Photo contributed)

At the peak of Diedrick’s life and in top physical shape, cancer hit him not once, but twice. The second battle ultimately claimed his life.

Just before the start of the 2014 season, his final one with the Montreal Alouettes, Diedrick’s family physician noticed that his white blood cell count was low. A subsequent bone marrow biopsy revealed a low hemoglobin level, and he was advised to undergo a liver biopsy.

That test revealed he had an enlarged spleen and was suffering from hepatosplenic gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma, a rare and aggressive type of cancer that begins in the spleen or liver.

Moulton recalled that her son spent the summer working out rigorously and was in the best shape of his career.

“All of a sudden, he became very ill,” she recounted. “He was sweating profusely and visibly struggling.”

Diedrick’s only hope lay in a stem cell transplant, and fortunately, his eldest daughter – Dominique -- was his only compatible donor.

Performed at Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, the procedure cost almost Can$1 million.

“That was just for the operation,” Moulton said. “I had to take a leave of absence from my job to travel to Buffalo to be with him. I started his IV before he went to the hospital for the stem cell transplant. After he was discharged, he stayed in a hotel, and I did other medical things and cared for him.”

Even though the illness ended his playing career in 2014, Diedrick returned to football in 2017 as a strength and conditioning coach for the Toronto Argonauts who went on to win the Grey Cup, marking his fourth title.

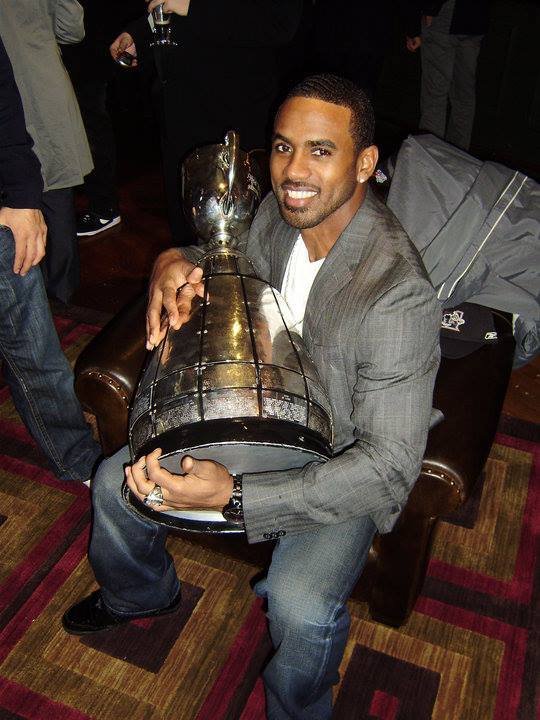

Illness ended Dahrran Diedrick’s CFL career in 2014 (Photo contributed)

After the procedure, he needed to receive a series of vaccinations because the transplant had wiped out much of his immune system, leaving him highly vulnerable to infections. These vaccines were crucial to rebuilding his immunity and protecting him from illnesses he would normally have been able to fight off.

After one of the vaccines, Diedrick noticed his arms were weak, and he began walking unsteadily, which worried his mother.

“I work in the medical field, and I know that if someone has an unsteady gait, it usually indicates a problem with the brain,” Moulton said, reflecting her immediate concern. “His doctor subsequently told him he had a variant of ALS. My son even asked for an MRI, but it wasn’t done then.”

In 2022, concerned about his health, Diedrick spent approximately Can$14,000 to get a second medical opinion at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota which is known for diagnosing and treating complicated or rare diseases.

“Dahrran said the doctors at the clinic simply reviewed his medical records from Toronto and did not perform any tests,” Moulton pointed out.

Travelling by airplane, she said, aggravated his condition.

After celebrating his younger daughter’s birthday in Green Bay, Wisconsin, Diedrick could not drive himself home from Toronto’s airport.

“Shortly after, at his friend’s bachelor party in Las Vegas that he went to with his best buddy Rome, Dahrran’s arm weakness was so severe that he required help dressing and managing other basic activities,” said Moulton. “After he came back home, I decided to go to the doctor with him.”

The moment they stepped into the physician’s office, he requested an MRI. The non-invasive scan was done three days later.

“I will never forget the day Dahrran’s partner called me to say he was being admitted to the hospital because the scan had revealed a brain tumour,” noted Moulton. “She said the doctors told her it was too large to operate on.”

A biopsy later confirmed that it was B-cell lymphoma, a type of cancer that affects the white blood cells responsible for producing antibodies and plays a key role in the immune system. While B-cell lymphoma usually originates in the lymphatic system, in Diedrick’s case, it had spread to his brain, making it a primary central nervous system lymphoma.

Six months after his death, the family started the DD Starlight Foundation to keep his memory alive and offer educational programs, scholarships and mentorship for young people from mainly marginalized communities who need support.

Born in St. Ann, Jamaica, the same parish that produced Marcus Garvey, Bob Marley and award-winning actress Sheryl Lee Ralph, Diedrick was raised by his maternal grandmother after Moulton left for Canada in search of better opportunities when he was three. He joined her four years later and discovered his passion for football at age nine.

“He started playing with older boys and tried to get on with clubs, but he was too young,” she said. “After a race with a boy who played football, he won and remarked, ‘if I can beat him in a race and he plays football, then I can be better than him at football’.”

Before entering high school at Cedarbrae Collegiate Institute, Moulton said her son wrote the goals he wanted to accomplish. High on the list was playing in the National Football League (NFL) and winning the Heisman Trophy, presented annually to the most outstanding player in American college football.

Although Diedrick was mentioned as a Heisman candidate in preseason and early-season discussions during 2001 and 2002, largely due to leading the Big 12 in rushing in 2001, he did not advance to become a finalist.

He spent time with the San Diego Chargers, Green Bay Packers and the Washington Commanders, but was released after appearing in one NFL game with Washington against the Minnesota Vikings on Boxing Day in 2004.

Nebraska's first Canadian scholarship recruit in 1998, Diedrick was the first Canadian to ever be the starting I-back in the Cornhuskers' heralded wishbone offence which is one of the prestigious positions in American college football because of Nebraska's commitment to the running game.

As a junior in 2002, he rushed for 1,299 yards to help Nebraska reached the BCS national championship game which they lost 37-14 to the Miami Hurricanes.

An excellent student, Diedrick was one of five Cornhuskers who played the season with a degree in hand. He earned his undergraduate degree in criminal justice studies in December 2001, finishing with a 3.165 cumulative GPA (Grade Point Average).

Last September, he was posthumously inducted into the University of Nebraska Football Hall of Fame. Moulton, who used two weeks of her vacation to travel to the United States so she could watch him play two games, attended the ceremony with her granddaughters, Dominique and Islie Diedrick, as well as her son’s partner.

Dahrran Diedrick and his son Kendrick (Photo contributed)

Diedrick’s son, Kendrick Diedrick, is a defensive lineman with the University of British Columbia football team.

“It was heartening to see how much Dahrran was loved and appreciated,” Moulton said. “However, the fact that he wasn’t there to receive his flowers made the moment bittersweet.”

Karen Moulton attended her son’s induction ceremony in Nebraska last September (Photo by Ron Fanfair)

Picked 24th by the Edmonton Eskimos in the 2002 CFL draft, Diedrick did not join the club immediately. Instead, he tried to make it in the NFL before returning to Canada in 2005 and joining the Eskimos that won the Grey Cup that season.

In 2006, he joined the Montreal Alouettes as a mid-season free agent and went on to spend five seasons with the club which won back-to-back Grey Cups in 2009 and 2010.

Traded to the Hamiton Tiger Cats mid-season in 2013, Diedrick played nine games before returning to Montreal in 2014 where his last season was limited because of ill health. In 130 CFL games, he rushed for 872 yards and six touchdowns on 179 carries.

Four-time Grey Cup winner Dahrran Diedrick (Photo contributed)

His football numbers in the United States and Canada may not tell a star’s story, but his character did, and that is how his mother and nearly everyone who crossed paths with him will remember him.

“Dahrran was incredibly kind and someone who would help anyone without hesitation,” Moulton said. “When he learned that the kids next door played hockey, he helped get them into a structured program where they could truly thrive. If he came across a child who was slow to come into their own, he would take the time to build their confidence. He was never too busy for anyone, and his ability to listen allowed him to understand others deeply and earn their trust.”

Just as Diedrick took time to encourage a child or guide them toward success, he treated everyone with the same warmth and attentiveness.

At the 2009 Grey Cup parade in Montreal, Ryan Snickars – who had a backstage pass -- experienced this first-hand.

“I was shy and didn’t want to bother anyone,” he recounted. “But Dahrran walked up, hugged me like a brother and started a 10-minute conversation, encouraging me not to be shy and talk to the rest of the guys.”

Dahrran Diedrick and Ryan Snickars in 2009 (Photo contributed)

On the field, Diedrick ran for yards. Off the field, he ran toward every opportunity to help, mentor and inspire.